Ol’ Jack Frightenum lived in the woods, on his own.

Not a hermit, for he took visitors and drank in local pubs and ran errands for himself. And he went to the Post Office, to collect his pension and write to the King. But he was always a solitary man and lived alone in his makeshift shack in Pound Lane Wood at Cadmore End for nigh on 20 years until a stroke took him when he was almost 90.

This is our tribute to Jack.

John Butler

Born 10th February, 1846, at Cadmore End, Lewknor Uphill.

Died 15th January, 1936, in Pound Wood, Cadmore End, one month short of his 90th birthday.

Interred at St Mary-le-Moor, Cadmore End.

JACK’S STORY

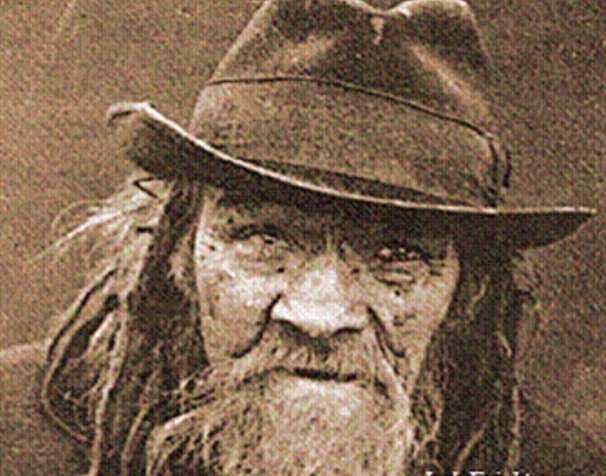

See his picture, how he gazes out at you. There is fire there, and wisdom, that only a life in the lap of Mother Nature can teach you.

Not that Ol’ Jack was not an educated man. He attended lessons sure enough and could read and write. Whether he was taught at school in Bledlow, or at the workhouse in Saunderton, or both, we cannot tell.

You could travel the world and still see no more than those eyes must have witnessed in the little woodland at Cadmore End. By day and, doubtless, by night, Jack would wander the woods, gathering fallen timber which he tied into bundles and sold as firelighters. Those who did not know of him would be alarmed to see a stooping, hatted figure, loping through the trees, hair matted almost to his waist, clothes shabbied with constant wear. Even locals would be startled if they came upon him on a sudden. No wonder they called him Frightenum.

Yet there was no harm in him. At least, no more than a life of poverty might grind into you, no matter how harmoniously you lived with the seasons and the land.

He was God-fearing too, studying his bible and always attending church. But perhaps God was his only fear, for he would boldly take issue with the preacher in the middle of his sermon if ever the man of the cloth strayed too far from the Word as Jack understood it.

They say he pledged himself to solitude after having his heart broken by the love of his life. But They don’t know. They are on more sure ground when They tell us that the good vicar of Radnage, governor of the workhouse at Saunderton where Jack spent much of his early life, found Jack lodgings with the Styles family at Liddies Bottom in Radnage Common.

Jack, we are told, was clean, honest and well-mannered and loved helping with the children. But all men must find their own ground and after a time Jack left to take up lodgings alone in a cottage on Cadmore End Common.

Here he stayed for many years, eking out a living from his wits, work and will power. A near neighbour, Mrs Amos Harman, is said to have shown him great kindness, preparing him a bowl of soup every evening. But now we start to hear tell of the toll that a life led on the edges can take, for if the soup was not forthcoming Ol’ Jack would not strive to conceal his disappointment. “He would,” They say, “carry on No End.”

Who can tell whether Jack struggled with the injustice that makes poverty beget poverty, or whether he simply had a taste for an easy life? Whatever the truth, the time came when he fell so far behind with his rent that he was forced to leave his cottage. He returned from his erranding one day to find the windows and doors removed from his home and the cavities stopped up with blackthorn bushes.

Once again the good people of Cadmore End took pity on him. There must be something in the Chilterny chalk. Mr Bird at Kenshams Farm gave Jack the use of an old chicken house on wheels, which he diligently cleaned and restored as best he good. Here he roosted for several years until this home too finally succumbed to the ravages of wind and rain.

Now Jack was getting old. He was near his 68th year when he was finally obliged to fly his wheeled coop and it seemed that the workhouse would claim him again. Not Ol’ Jack though. Instead, he roamed the woodland that time had woven into his bones and from it brought timber that he could fashion into a ramshackle abode. He made Pound Bottom Wood his home and there he stayed for many more years.

How the wind does blow on the ridges of the Chilterns, though, and especially this ridge, right on the edges of the Oxfordshire plain. Jack’s shack was no match for the gales curving up from the low-lying land and one hard winter he was overtaken by pneumonia. This time, even tough Ol’ Jack Frightenum could not stave off the workhouse’s perennial pull on the poor of the land and he was taken away to be cared for properly.

“Poor Ol’ Jack,” They said. “He was a one.” And They shared tales of the sumptuous dinner he had thrown for his friends at The Old Ship when his mother left him £100 in her will, and of the coronation party for King George V, where Jack pranced merrily – perhaps a little too merrily – round the huge bonfire on the common. Poor Ol’ Jack Frightenum. They would not see his like again.

It was true enough. For They saw not his like, but Ol’ Jack himself, shambling back to his bosky haunts, fully recovered, and wiry, gimlet-eyed and cantankerous as ever he was. Say what you like about the workhouse, they’d done their best for Ol’ Jack Frightenum, even though he would have none of the ghastly green “jollop” they tried to inflict upon him.

His windblown shack was gone, but he simply set about building another on the same spot. And this time, either his handiwork was better or the weather looked more kindly on him, for here he stayed for the last 20 years of his life.

Age only wearies us if we let it, but it does make us more honest and true. When Father Time and Mother Nature loom larger in your daily comings and goings, you have less inclination to fuss over the social niceties. You speak your truth and meet the world on your own terms. So it’s easy to see why Ol’ Jack, never one to worry too much about airs and graces, worried less and less about matters of personal hygiene as he passed well beyond his allotted three score years and ten.

They say that one kindly old woman took him two woollen vests to stave off the winter chill and as he thanked her he simply put one of them on over the clothes he was already wearing. Who would blame him if he never changed his vestments in the cold season? Even in our snug centrally-heated homes, there’s many a morning when we divest ourselves of cosy pyjamas to step gingerly into chilly clothing. Ol’ Jack wasn’t daft, count on it.

Other neighbours also made sure he had warm clothes and blankets. Mrs. Clarke, who lived at the White House in Bolter End, regularly took Jack a hot meal on Sundays and the Plumridge family had him round for tea most Wednesdays. He always took sweets for the young Plumridges, but his long hair, odorous clothes and intense demeanour made him an uncomfortable presence for the little ones.

Mind you, Jack was never a man to rely on handouts for his keeping. He eked a living as a woodcutter, gathering twigs and branches and fashioning them into faggots that served well as kindling. He bound his neatly trimmed sticks into bundles tied with withes, which he made from strips of willow and hazel. He always kept some back for his own supply. They made an arcing shelter for him as he sat outside his shack in the gloaming by his fire.

The little cash he earned kept him in groceries and every Saturday he would walk in to Warren’s in Lane End to stock up. He was often seen sitting on a large stone by the side of the Finings Road, eating the sweets he bought. Like many folk who work hard for a meagre living Jack was a generous soul and would share his treats with the children who came prattling by with their families. He might slip a penny into their hands as well.

Over the years his fame – or was it notoriety? – spread and he became a regular stop for walkers through his wood. He obligingly kept the paths around his hut trim and tidy and always had sticky sweetmeats to offer any children among the families strolling by. Not that they were the treats he intended them to be; one glance at the aging and dirty tin was enough to tell even the most eager recipient that perhaps the sweet was best not eaten there and then. Most learned to accept the gift gratefully and duly dispose it of once they were out of sight of their alarming but kindly benefactor.

He had more to share than sweets, too, did Ol’ Jack. One young visitor, up from London to stay with a friend in Cadmore End, spent an afternoon chatting happily with Jack outside his hut, only to find herself scratching vigorously by the time she got home. Close inspection showed that some of what locals called “Jack’s livestock” had hitched a ride on the hapless guest.

Another young girl, blessed with lustrous blonde hair, was more fortunate. Jack’s gift to her was the tale of Samson, whose strength deserted him when his hair was cut. Jack’s piercing gaze fixed hers and he gave a stern warning never to make the same mistake.

There are no better teachers than the land and the seasons. Jack lived his life close to both, and close to his God. Many folk said he proclaimed himself a prophet and foretold the time when “men would eat grass”. When children game gambolling through the wood in early summer, and stopped to pick the bluebells that carpeted the floor, Jack would come grumbling after them, berating them for “stealing God’s flowers…”

Jack’s schooling always served him well. He could read his bible and he wrote prolifically, though his writings were lost after he passed away. Not all of them, mind. Somewhere in the files at Whitehall a budding Sir Humphrey may one day chance upon the letters Jack wrote to the King and to the Prime Minister about the injustices and wrongdoings of the world. There will be no record of any reply, though. Jack always declared that they were too scared to take him on and who would be so bold as to suggest otherwise?

Among the most vitriolic of his epistles was the one he wrote during the epidemic of foot and mouth disease in 1930. Compassionate, principled Jack was enraged by the sight of healthy animals being destroyed and the devastation it brought upon his neighbours on the local farms. He marched into the Post Office and demanded a pen and paper, with which he dispatched a withering letter of reprimand to Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald.

For all his forthright passion, Jack was never one to let his speech run away from him. We’re told that the foulest of his language was the imprecation “boller”, his bucolic take on “bother”. He said it often enough, mind, to earn himself another nickname; Ol’ Jack Frightenum was also known as Ol’ Boller.

It was a winter’s day in 1936 that Ol’ Jack Frightenum passed away. They found him ill and fading and summoned a doctor from Lane End, who eased him into eternity as best he could. And so he was laid to rest in the churchyard he knew so well, attended only by Rose Druce, whose husband was related to Jack’s father Richard, and her sister-in-law Lillian, who ran The Old Ship pub where Jack had many a time warmed himself malodorously by the fire.

Jack Butler believed he would live forever, in the care of his God. And perhaps he does, though he walks the wood no more. At least, no one has seen his stooped, lean figure walking the paths that his own feet may first have marked across Pound Bottom Wood, Leygrove Wood and Cadmore End Common.

But that may be because they do not have the eyes to see. For all we know, Ol’ Jack Frightenum lives there still, and always will.

Thank you it was a joy to learn about Jack. I am indebted to my work colleague Darren Hayday for introducing me to the story.

LikeLike

What a beautifully written piece. Always been a fascinating story and you yave managed to bring it to life. Thank you

LikeLike

I also think it’s lovely that the children knew he was harmless. He clearly had a good heart. By the way, my mother was at school with Judith Plumridge whose address she remembers as ‘Near Church’ Cadmore End. Any relation?

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment. It’s a lovely addition to the story!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this lovely version of this story. My grandmother was a Plumridge and my family originate from Cadmore End. My mum and her sisters were often told by their dad to “go to sleep before I get Jack Frightenum round” but they knew him to be harmless. My own children are fascinated by the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person